Supervised learning¶

Introduction¶

“Supervised learning” refers to building a model with a data set that includes records that have values for a response variable of interest (for example, crop yield), and for predictor variables (for example, rainfall and fertilizer application rates).

In matrix notation these models have the form \(\hat{Y} = \hat{f}(X) + \epsilon\), where \(\hat{Y}\) (Y-hat) is a vector of model predictions for the variable of interest; \(X\) is the matrix with predictor variables; and \(\epsilon\) (epsilon) is the unexplained variation. The art is to find the most appropriate function \(\hat{f}\) (f-hat) — that is the one that most closely resembles the true function \(f\). In the next paragraph, we illustrate that the best model is not necessarily the model that minimizes the unexplained variation (\(\epsilon\)).

Over-fitting versus under-fitting¶

linear regression model¶

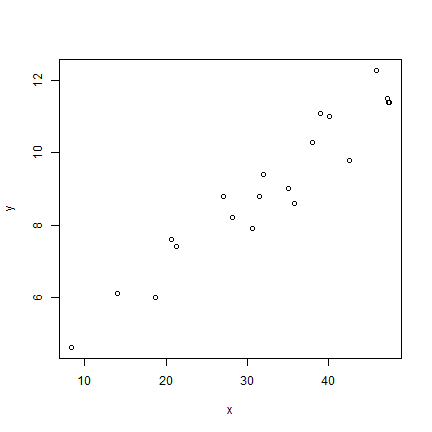

Over-fitting a model means that the model fits the data that was used to

build the model very well — in fact too good. Let’s look at that with a

simple data set where we have a response variable y and a single

predictor variable x.

x <- c(35, 47.2, 20.7, 27.1, 42.5, 40.1, 28.2, 35.8, 47.4,

21.3, 39, 30.6, 18.7, 8.4, 45.8, 14, 47.3, 31.5, 38, 32)

y <- c(9, 11.5, 7.6, 8.8, 9.8, 11, 8.2, 8.6, 11.4, 7.4,

11.1, 7.9, 6, 4.6, 12.3, 6.1, 11.4, 8.8, 10.3, 9.4)

plot(x, y)

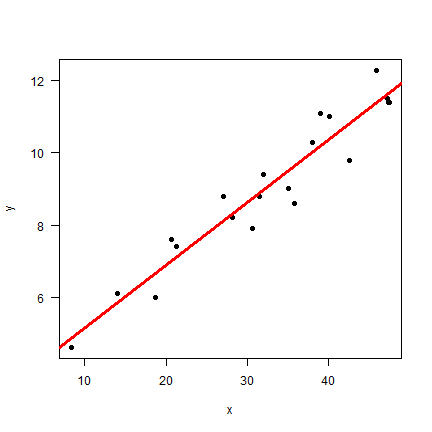

We could build a simple linear regression model like this

mlr <- lm(y~x)

plot(x, y, pch=20, cex=1.5, las=1)

abline(mlr, col="red", lwd=3)

summary(mlr)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.02846 -0.32128 -0.09411 0.47323 0.93314

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3.4050 0.4266 7.982 2.53e-07 ***

## x 0.1738 0.0124 14.021 3.97e-11 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.6214 on 18 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.9161, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9115

## F-statistic: 196.6 on 1 and 18 DF, p-value: 3.967e-11

A linear regression model takes the form \(\hat{y} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + ...\) where \(\beta_0\) is the intercept and the other \(\beta\)s are slopes. In this case we found \(\hat{f}\) to be y = 3.4 + 0.17x.

I hope you will agree that this looks very good. The line seems to capture the general trend; the model R2-0.92, and the p-values for the model parameters are very small (strong support for the intercept and slope being unequal to zero). But can we do better?

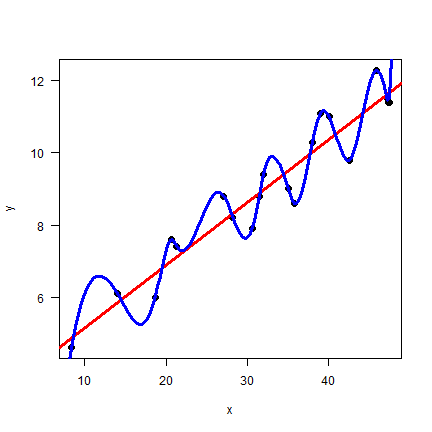

Spline model¶

Linear regression models with a single predictor variable are not very flexible. Let’s try another extreme, a spline function. A spline model is referred as a non-parametric model (this is a misnomer, it has, in fact, a lot of parameters, so many that we do not want to consider them, as we cannot easily interpret them).

# create the function from the data

sf <- splinefun(x, y)

# x prediction points

px <- seq(1, 50, 0.25)

# predictions

py <- sf(px)

plot(x, y, pch=20, cex=2, las=1)

abline(mlr, col="red", lwd=3)

lines(px, py, col="blue", lwd=3)

Wow. Model sf seems perfect. Let’s compare the two models with the

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) statistic.

Root Mean Squared Error¶

The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is a commonly used metric to compare models with a quantiative repsonse. For qualitative responses measures such as kappa are used, and if the response if true/false (presence/absence) ROC-AUC is commonly used.

Here is a function that implements RMSE.

rmse <- function(obs, prd, na.rm=FALSE) {

sqrt(mean((obs - prd)^2, na.rm=na.rm))

}

Let’s test this new function. We have observed values of 1 to 10, and a three different predictions.

# no difference, perfect model

rmse(1:10, 1:10)

## [1] 0

# a small difference, not bad

rmse(1:10, 2:11)

## [1] 1

# rather different, much worse than the above

rmse(1:10, 10:1)

## [1] 5.744563

So the more different the observed and predicted data are, the higher the RMSE. The scale of the RMSE is in units of the data. To make it easier to interpret RMSE values, you can express them relative to a Null model. A Null model is a simple, perhaps naive model, that can serve as an important benchmark. To evaluate a complex model it is often not of prime interest to know how good it does, but rather how much better it does than a Null model.

With the example data above, a good Null Model might be the mean value of the observed data.

null <- rmse(1:10, mean(1:10))

null

## [1] 2.872281

A function that computes the RMSE relative to a NULL model could look like this.

rmsenull <- function(obs, pred, na.rm=FALSE) {

r <- rmse(obs, pred, na.rm=na.rm)

null <- rmse(obs, mean(obs))

(null - r) / null

}

Let’s use it.

rmsenull(1:10, 1:10)

## [1] 1

rmsenull(1:10, 2:11)

## [1] 0.6518447

rmsenull(1:10, 10:1)

## [1] -1

A perfect model explains 100% of the RMSE of the Null model. In the

example above, the prediction 2:11 explains 65% of the Null model.

That is very good! The prediction 10:1 is worse than the Null

model.

Compare models¶

Now we can use our rmsenull method with our two models, and compare

their performance.

For the linear regression model

plr <- predict(mlr, data.frame(x=x))

rmsenull(y, plr)

## [1] 0.7103717

And for the spline model

psf <- sf(x)

rmsenull(y, psf)

## [1] 1

By this measure, the spline model is perfect. The linear regression model might still be fit for purpose, but it does not look as good as the spline model.

However, we made a major mistake in our model evaluation procedure. We should not evaluate the model with the same data that we used to build the model. Because if we do so, we are guarenteed to select models that are overfit. To illustrate this, let’s split the data in a two samples (this is not generally the best practise, see the section on cross-validation).

n <- length(x)

set.seed(321)

i <- sample(n, 0.5 * n)

i

## [1] 18 13 16 17 4 15 11 9 12 2

xa <- x[i]

ya <- y[i]

xb <- x[-i]

yb <- y[-i]

Now train (fit) and test (evaluate) the models again. First use sample “a” to train and sample “b” to test.

mlr_a <- lm(ya~xa)

sf_a <- splinefun(xa, ya)

plr_a <- predict(mlr_a, data.frame(xa=xb))

psf_a <- sf_a(xb)

rmsenull(yb, plr_a)

## [1] 0.6423837

rmsenull(yb, psf_a)

## [1] -0.929826

Now use sample “a” to test and sample “b” to train.

mlr_b <- lm(yb~xb)

sf_b <- splinefun(xb, yb)

plr_b <- predict(mlr_b, data.frame(xb=xa))

psf_b <- sf_b(xa)

rmsenull(ya, psf_b)

## [1] -2.512748

rmsenull(ya, plr_b)

## [1] 0.7028963

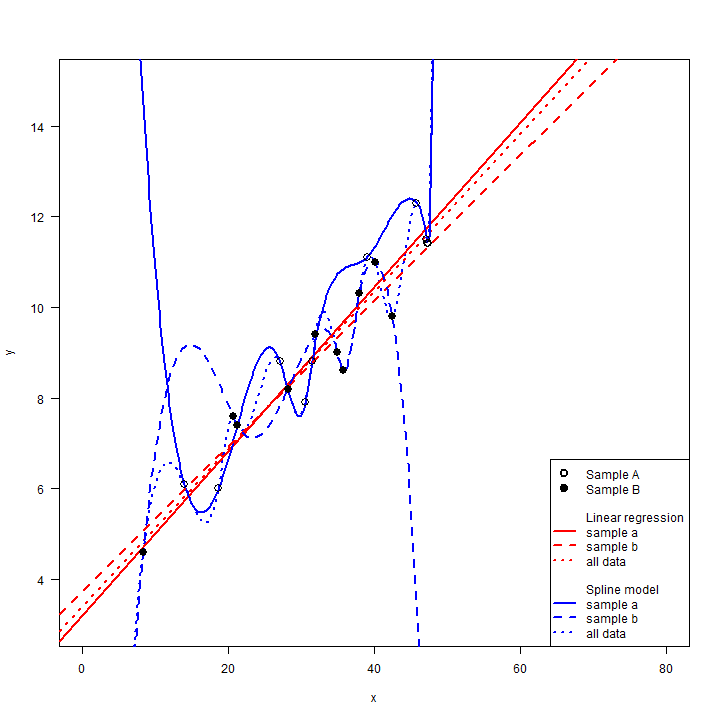

In both cases the linear regression model peforms much better. The mean RMSE, relative to the Null model, for the linear regression model is ( 0.64 + 0.7 )/2 = 0.67, much smaller than for the the spline model ( -0.93 + -2.51 )/2 = -1.72. Also note that the RMSE for the linear regression model is similar to the RMSE computed with the model training data when it was fit will all data (0.71). That is also easy to see visually.

#set up the plot

plot(x, y, las=1, cex=0, xlim=c(0,80), ylim=c(3,15))

# original models

abline(mlr, col="red", lwd=2, lty=3)

lines(px, py, col="blue", lwd=2, lty=3)

# sample A models

abline(mlr_a, lwd=2, col="red")

lines(px, sf_a(px), lwd=2, col="blue")

# sample B models

abline(mlr_b, lwd=2, col="red", lty=2)

lines(px, sf_b(px), lwd=2, col="blue", lty=2)

# sample A and B points

points(xa, ya, cex=1.5)

points(xb, yb, cex=1.5, pch=19)

# a complex legend

legend("bottomright", pch=c(1,19,rep(NA, 10)), lty=c(NA, NA, rep(c(NA, NA,1,2,3),2)), lwd=2, , pt.cex=1.5, bg="white",

legend=c("Sample A", "Sample B", "", "Linear regression", "sample a", "sample b", "all data", "", "Spline model", "sample a", "sample b", "all data"),

col=c("black", "black", "white", "white", rep("red", 3), "white", "white", rep("blue", 3))

)

The spline model fit the training data perfectly, but that made it

predict spectacularly bad for some of testing data. The linear

regression model is not very flexible, so it did not change much when it

only got the subset of data. This is an important feature. The linear

model has low variance. That is, the estimated model does not change

much when it is estimated with slightly different input data (do not

confuse this use of the word “variance” with how it can be used to

describe variability in a sample of quantitative observations). This is

very important as a model only has value if it has some generality, not

if it just fits a particular dataset. Note that the RMSE are essteniall

for an interpolation problem. When x is between 15 and 40, the

spline model is much worse than the linear regression model, but the

three models (all data, sample A, and sample B) are somewhat similar.

However, if we were to use these models for extrapolation (in practical

terms, think predicting to a different region, group of people, time

period), the results would be dramatically unreliable as the different

spline models show extreme, but opposite responses. This does not mean

that the linear model is right — we have no data for x < 8 or x > 48.

The true model¶

Well, in this case, we actually do have . The data for x and y

were sampled (and then rounded to 1 decimal) from a known function —

we do not have these for the real world. But we can use functions like

that to generate data to learn about modeling methods. We used the

function f below to generate the data used in this section.

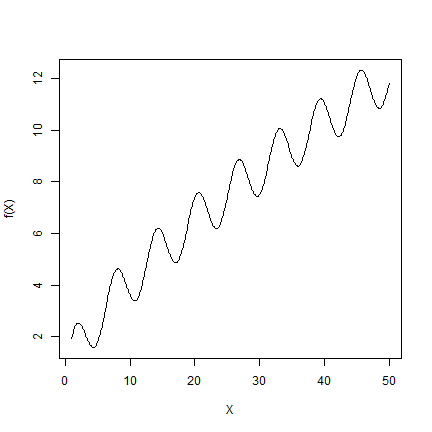

f <- function(x) x/10 + sin(x) + sqrt(x)

X <- seq(1,50,0.1)

plot(X, f(X), type="l")

And the following procedure to create the sample data.

set.seed(2)

sx <- sample(X, 20)

sy <- f(sx)

So, the linear model clearly was wrong. But, then, all model are wrong. Some models are more useful than others, and the linear model might be close enough to be fit for purpose.

Can flexible models be good?¶

So is a single variable linear regression always better than a spline model? No. It depends. It depends on how linear the relationship between x and y, and it also depends on the sample size. The more complex the model, and the larger the sample size, the better the spline might do. Here is simple example where the spline model does better.

The true model:

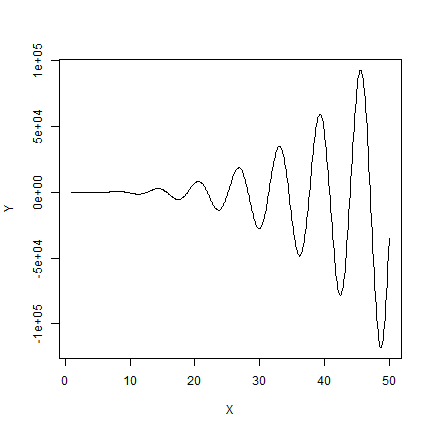

f <- function(x) {x - x^2 + x^3*sin(x)}

X <- seq(1,50,0.1)

Y <- f(X)

plot(X, Y, type="l")

Two samples from the true model. Here we do not add error to the data —

but that is often done to simulate the effect of measurment error. It is

easy to do with a function like runif or rnorm.

set.seed(2)

xa <- sample(X, 40)

ya <- f(xa)

xb <- sample(X, 40)

yb <- f(xb)

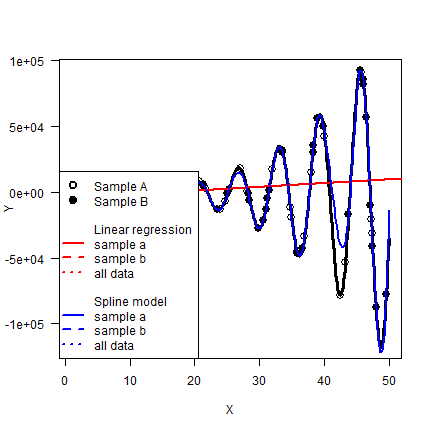

And compare the two models again

mlr <- lm(ya~xa)

sf <- splinefun(xa, ya)

rmsenull(yb, predict(mlr, data.frame(xa=xb)))

## [1] -0.0312567

rmsenull(yb, sf(xb))

## [1] 0.8082887

mlr <- lm(yb~xb)

sf <- splinefun(xb, yb)

rmsenull(ya, predict(mlr, data.frame(xb=xa)))

## [1] -0.04616483

rmsenull(ya, sf(xa))

## [1] 0.7672714

In both instances, the spline model RSME is about five times smaller.

px <- seq(1, 50, 0.25)

py <- sf(px)

plot(X, Y, type="l", lwd=3, las=1)

points(xa, ya, cex=1.5)

points(xb, yb, pch=19, cex=1.5)

abline(mlr, col="red", lwd=2)

lines(px, py, col="blue", lwd=2)

legend("bottomleft", pch=c(1,19,rep(NA, 10)), lty=c(NA, NA, rep(c(NA, NA,1,2,3),2)), lwd=2, , pt.cex=1.5, bg="white",

legend=c("Sample A", "Sample B", "", "Linear regression", "sample a", "sample b", "all data", "", "Spline model", "sample a", "sample b", "all data"),

col=c("black", "black", "white", "white", rep("red", 3), "white", "white", rep("blue", 3))

)

What have we learned?¶

We should note that these stylized examples have little to do with real

data, where you might have a lot of noise and multiple observations for

y for each x. Perhaps you can look at that in a simulation of

your own? But we hope that this section helped illustrate (a) the risk

of overfitting; (b) that models should be evaluated with data that was

not used to train the model.

There is much more to say about linear regression. In practice you often have many predictor variables. Or you can create new pridictor variables by creating squares and cubes, or interactions. For example, you can do

mlr <- lm(ya ~ xa+I(xa^2)+I(xa^3))

With each parameter you add flexibility to the model. That can lead to overfitting, and a loss of interpretability. See the sections on stepwise model selection, and on lasso and ridge regression in ISLR for detailed discussion.

Like in lasso and ridge regression, spline models can be constrained (made less flexible) through some form of regularization. In these “smoothing spline” models, there is a penalty function that reduces the amount of flexibility.

Complex models¶

There are various algorithms than can be used to make relatively complex models for predictions with large data sets, with many variables, of which several may contribute to the model, perhaps with complex interactions, and likely noisy data. Popular examples of such (“machine learning”) algorithms include Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN).

The next chapter focuses on the Random Forest algorithm as an example.

Citation¶

Hijmans, R.J., 2019. Statistical modeling. In: Hijmans, R.J. and J. Chamberlin. Regional Agronomy: a pratical handbook. CIMMYT. https:/reagro.org/tools/statistical/